A motion picture director may use a shot to serve a number of purposes, such as establishing characters, photographic qualities and film style. Any one shot in an entire movie made up of hundreds or thousands of shots produces meaning through more than just acting, dialogue and music. A shot is constructed of many cinematic elements that make up the mise-en-scene. Meaning is conveyed from the shot’s context and where it is placed through editing in the relation to other shots and the general narrative of the film. In this article I will explore several aspects related to the construction of a shot in the 1927 movie ‘Sunrise A Song of Two Humans’, directed by German Expressionist F. W. Murnau at the end of the silent film era in Hollywood. The shot that I explore here occurs towards the end of the narrative. It is very similar to a shot that occurs towards the beginning of the narrative. The main difference between the two shots is the performance of the lead actor, George O’Brien. It is a technique used by directors known as the parallel shot. The shot that I’m exploring is probably the most emblematic of the central theme of the Sunrise: to cherish what we have and be careful what we wish for.

In their text Film Art. An Introduction (2012) David Bordwell and Kristen Thompson define the mise-en-scene as 'the arrangement of people, places and objects to be filmed.'

The mise-en-scene of a shot is made up of how it is lit, where it is set, the costumes and makeup, props, the composition, camera techniques seen by the audience, and of the actors. It is with a humble understanding of all this that I breakdown the particularity of the shot I have chosen to discuss, while also considering Sunrise in general and other shots that contribute to the meaning the audience may read from the shot.

I turn now to make some sense of the plan in the film and how this might fit into the broader patterns of form and style that structure the film. Bordwell and Thompson define form as 'the sum of all the parts of the film, unified and given shape by patterns such as repetition and variation, story lines, and character traits.'

The shot: The man in the bedroom

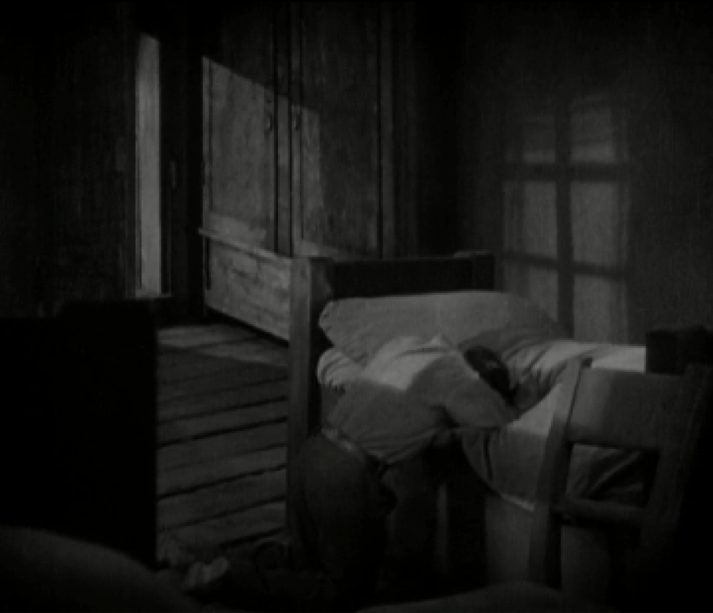

The shot begins with the empty bedroom of O'Brien's character simply credited as 'The man'. The camera, angled mid-height, is positioned opposite a door and does not move throughout the shot. Part of the man's bed is out of the bottom left frame while, opposite, 'The wife's' bed occupies most of the frame. (See Image 1 below)

Image 1. The dark, empty room. The wife's bed is given importance by the function of the lighting and composition, her bed occupies the frame while the husband's is cropped out. It is also well lit with high key lighting, with the image of a cross made by the shadow of the window, a symbol of the good nature of the wife thought to be deceased. Light also enters through the doorway in the background, providing a low-key light for the floorboards, giving a sense of depth to the room.

According to Bordwell and Thompson directors exploit four major aspects of lighting: its quality, direction, source, and colour.

“The filmmaker will create a lighting design that seems consistent with the sources in the setting.” (Film Art An Introduction (2012)

In the shot pictured above the setting is dark and lit from a source representing the moon. The light enters through a window in the left of frame and casts the clearly defined shadow of a cross on the bed and wall behind it. The light is also directed on an open doorway in the background.

Image 2. A strong silhouette is cast on the wardrobe placed in the background.

A silhouette comes into sharp focus in the doorway before a man appears. (Image 2) He moves to the middle of the room and collapses to his knees, grief-stricken, hunched over his wife's bed. This is where the shot ends. (See Images 3 and 4)

Image 3. The man moves very slowly into the room, his shoulders slumped, he looks defeated. As he enters the light and notices the empty bed of his wife, who he thinks is dead.

Image 4. The man is overcome with grief and falls to his knees by the bed. He leans over the bed, an image of a man trying to hold onto what he thinks he's lost.

The shot occurs towards the end of the film, and is 42 seconds duration. In the context of the narrative paradigm this shot’s purpose is to show the emotional agony of the character in what screenwriter and author Jake Synder calls the movie’s ‘Dark Night of the Soul’ moment.

The construction of the shot

The function of the cinematic elements that make up the shot's mise-en-scene work to draw focus to O'Brien's performance. The shot is almost identical to another shot at the beginning of the film in lighting, composition, photographic quality and cinematography. Murnau has chosen to place great importance on the difference between the two parallel shots in context to one another in the narrative form.

Bordwell and Thompson say patterns and variations engage the audience to participate in the film.

“As the viewer watches the film, she or he picks up cues, recalls information, anticipates what will follow, and generally participates in the creation of the film's form. … the film shapes our expectations by summoning up curiosity, suspense, surprise, and other emotional qualities.” (Film Art An Introduction (2012)

Murnau has contrived to create a sense of familiarity between this and the earlier shot. Because the performance – the actor's movement and staging - is the only visual difference between the two shots this technique allows the audience to shape an expectation of what might happen.

Earlier in the narrative O’Brien’s The Man creeps into the bedroom after a secret extra-marital rendezvous with plans to drown his wife. He has agreed with his mistress to do so. Later, he changes his mind, but events conspire to cause his wife to drown accidentally, and so he returns to their marital bedroom racked with grief and guilt.

It is my reading of the shot that its construction summons our viewer curiosity, creates suspense, and gives an insight into the emotional journey of O'Brien's character by drawing focus to the actor's performance. We the viewer recognise the similarities of this shot to the one earlier and therefore we are already anticipating what might happen this time. Murnau wishes to convey The Man’s change of heart, he no longer wishes his wife were dead.

It is central to the shot's meaning that we know the husband is entering the room upon learning that his wife has drowned, and we are forced by our ability to recognise patterns to recall the parallel shot in which in O’Brien’s character earlier entered the room with thoughts of drowning his wife. If you only watched these two shots side by side and nothing else of the movie you will still know this movie is about a man who had a wife who later dies.

How the function of the cinematic elements convey meaning

Murnau has made very deliberate choices when it comes to how the function of costume, lighting, composition, and performance allow the audience to create meaning in their reading of the film.

Lighting can be used to hint at the true nature of a character. Referring to the film in general, the costume and lighting for the wife and the ‘Woman from the City’ are a deliberate juxtaposition between light and dark respectively. The wife, fair-haired, is always softly lit, the camera uses a soft filter and her costume consists of lighter hues. Throughout the narrative she only moves in the well-lit parts of the settings. By contrast, 'The Woman from the City’ has dark hair; constantly moves in the shadows, smokes, and her costumes are dark coloured.

The wife’s bed is lit in a soft white light and is often the brightest part of the frame. The moonlight shining through the window frame casts the shadow of a cross on the bed, symbolizing the wife’s good character. The element of the religious, the distinction between good and evil, and the sacrifice of an innocent are thus subtly foreshadowed by this lighting device. In this way the lighting adds deeper meaning to the shot as when the husband falls to his knees by his wife's bed it gives the impression of a sinner begging forgiveness from the divine.

The man's performance is stylised but together with the other elements of mise-en-scene function to convey his emotional turmoil.

How the technique of the parallel shot conveys meaning

According to Bordwell and Thompson ...

'... Any pattern of development will encourage the viewer to create specific expectations. … The pattern of development may also create surprise, the cheating of an expectation ...' - Film Art An Introduction (2012)

The use of the parallel shot and its position in the narrative paradigm allows the audience to see the irony and understand more deeply the character’s heartbreak. In this way the performance, technique and context of the shot in relation to the narrative form allows for the emotional impact of the husband’s grief to stir up greater emotional engagement by the audience.

The shot’s composition, lighting and O'Brien's performance are almost exactly the same as the previous shot. The composition of this shot is slightly tighter, cutting off most of the husband’s bed. This has the effect of focusing the audience’s attention on and gives greater importance to the empty bed of his wife.

The only element in the shot’s construction that is different between the parallel shots is the actor’s performance. The staging is the same however whereas before he snuck, staying to the shadows before falling into his own bed, now he shuffles, shoulders slumped before collapsing against his wife’s bed. This makes O'Brien's performance stand out in contrast to the elements that stay the same.

My understanding of what the film is about

‘Sunrise’ has a simple plot of a village married couple whose fidelity is fractured by the appearance of a temptress from the city. The temptress, ‘The Woman from the City,’ seduces the husband and convinces him to drown his wife. He agrees but later ends up remembering why he fell in love with her in the first place. Having spent the day rekindling their romance the irony of the situation and the weight of his foolishness hit both him and the audience hard in the parrallel shot when he returns to his bedroom after his wife accidentally drowns.

Final Thoughts

Murnau has chosen to use parallel shots as a technique to cue the audience to anticipate action, feel sympathy and other emotions; to read greater meaning from the shot. Murnau achieves this by controlling the function of lighting, composition, and performance to direct attention to elements of mise-en-scene. O'Brien's performance is stylised but retains a sense of realism even 80 years after the film was released; his loss is felt by the audience who know what choices he's made. The shot is constructed to show a turning point in the plot and the character's development. At the start of the narrative he desired to be free of his wife (by drowning her) and at the end of the narrative his wish came true, despite his best efforts to prevent it. In the one shot my understanding of what 'Sunrise' is about is visually conveyed by the image of 'The Man' kneeling before the shadow of the cross cast on his wife's bed; a symbol of her goodness, and a bitter reminder that he did not cherish what he had until it was gone.

Caden Pearson is a Writer/Director at Iron Gate Films in Far North Queensland, Australia. He recently wrote, directed and produced two short documentaries for the National Indigenous Television (NITV) series Our Stories, Our Way, Everyday. 'Norman Baird The Bama Digger' was produced through Iron Gate Films in mid-2015 and 'Doctor Gemma' was produced through Bacon Factory Films in late 2014. In late 2014 Caden was shortlisted for The Production Line Gold Coast Summer Series Masterclass with his short drama 'Samuel Star Wipe'. His short drama 'Good Catch' was screened at The Dreaming Festival in 2009, and licensed for broadcast on NITV in 2010. Caden also provided story development and script editing to short drama 'On Stage' (Directed by Ben Southwell, Turn Dog Quick Films) commissioned by Screen Australia through their Pitch Black Short Drama Production program, and screened at the Sydney Film Festival in 2015. His first award came from his short documentary 'Homeland' winning Highly Commended at the Queensland New Filmmakers Awards in 2004. With a background in news production and freelance filmmaking, he is enjoying the move to longer form documentary.